Scientist calculates odds alien life is common in the universe

If you could rerun Earth's history, a new analysis finds life is highly likely to emerge again. But intelligent life faces longer odds.

If Earth were cloned at the point of its formation, the odds are good that life would emerge. Intelligent life, not as much.

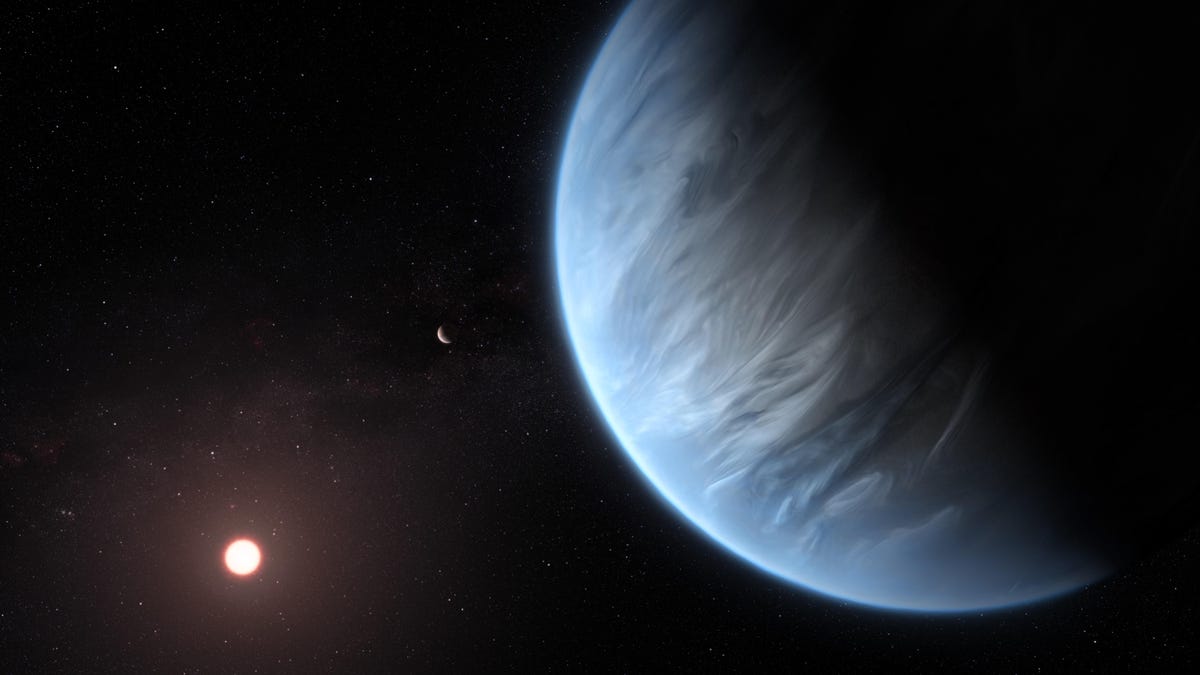

It's estimated that there could be in excess of 10 septillion (that's 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000) planets in the observable universe. And if any of those worlds are exact twins of Earth, the odds that they also host life are nine times better than the odds they're lifeless and barren.

That's according to a new analysis from Columbia University astronomy professor David Kipping. He ran the numbers and found that wagering that life will emerge on an Earth clone appears to be a pretty safe bet, but you might not want to risk your life savings on the chance that intelligent life will evolve.

In a paper published Monday in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, Kipping uses a tool from statistics called Bayesian inference to calculate the odds based on a few key assumptions and the existing data we have about life in the universe.

We know nothing about how frequently life and intelligent life emerge, if at all, on worlds beyond Earth. What we do know is that life emerged on Earth fairly early in our planet's long history. Conversely, though, intelligent life only started mucking about and making tools ranging from the wheel to particle accelerators in the most recent chapter of Earth's biography. Really in the last line of that story.

Maybe the gestation of intelligence is a very long (4 billion-year) process, or maybe that's just the way it worked out for Earth. Kipping wondered how often life and intelligent life would emerge on our planet if we were able to turn back the clock on our planet's history and then run it forward over and over again.

To analyze the problem, he came up with four possible answers: Life is common and often develops intelligence. Life is rare but often develops intelligence. Life is common and rarely develops intelligence. And finally, life is rare and rarely develops intelligence.

Kipping found that every time he ran the numbers, the odds that life is common were always at least nine times better than the odds life is rare.

"We have a rather profound conclusion here that life is most likely common," he says in the above video, which also offers a deeper dive into his analysis.

Interestingly, however, the odds that intelligent life would develop as it has to give us light-speed global communications, Sriracha sauce, and the words of Pablo Neruda among countless other items in the catalog of awesome are a little different.

"If we played Earth's history again, the emergence of intelligence is actually somewhat unlikely," Kipping says. "My bet is that life is common, but intelligent life may be rare."

So this means that if we were to extrapolate the analysis to the larger universe, many planets may be inhabited, but their occupants could be no more exciting than some bacteria in the dirt or lichen on the rocks.

Kipping cautions that his work shouldn't be taken as proof the cosmos has an abundance of aliens, because we're still relying on what we know of life emerging on just one isolated world -- Earth. If it turns out that Earth twins are rare in the universe, it doesn't really matter that they're a good bet for generating life.

"Yet encouragingly, the case for a universe teeming with life emerges as the favored bet," Kipping concludes. "The search for intelligent life in worlds beyond Earth should be by no means discouraged."