Kepler: Finding a 'Goldilocks zone' in the Milky Way

NASA is just hours away from sending up a spacecraft on a mission to stare at thousands of stars in the hopes of finding an Earth-like planet or two.

In the vastness of the universe, there are likely to be nearly countless planets. The big question for humans, of course, is whether even a single one of them could support life.

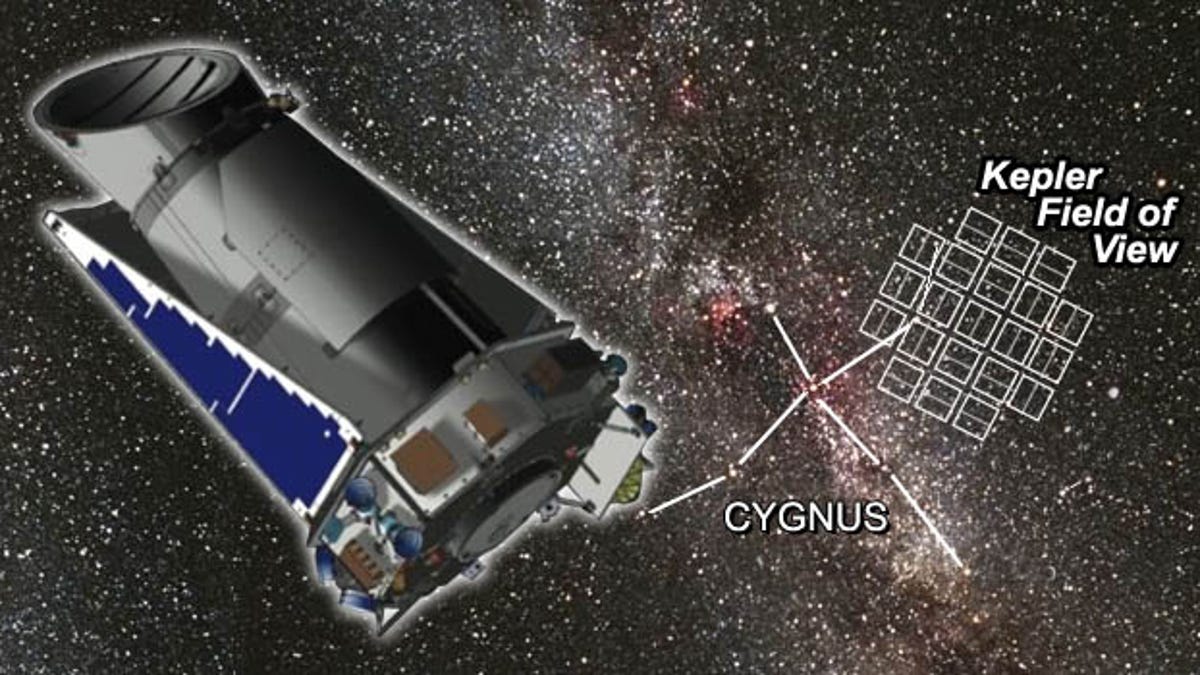

NASA's Kepler satellite, which is scheduled to lift off at 10:49 p.m. EST tonight, is headed out to keep watch on a patch of the Milky Way for at least three and a half years. Unlike the Hubble space telescope, Kepler won't be taking brilliant pictures suitable for framing. Instead, it will look for minute changes in the brightness of stars--some 100,000 of them--that would indicate a planet passing in front.

Of all the planets Kepler eventually finds, what NASA is most interested in are planets like Earth. That is, it's looking for rocky orbs--from half as large to twice as large as our big blue marble--in the habitable zone around a given star where conditions might be amenable to folks like us, or at least some of our fellow earthly organisms.

"The habitable zone is where we think water will be," Bill Borucki, Kepler principal investigator at NASA Ames, says in a video on the space agency's Kepler site. "If you can find liquid water on the surface we think we may very well find life there. So that zone is not too close to the star, because it's too hot and water boils, and not too far away where the water is condensed...a planet covered with glaciers. It's the Goldilocks zone--not too hot, not too cold, just right for life."

To scope out the interstellar terrain, Kepler will use its photometer--essentially, an oversize light meter--equipped with 42 charged coupled devices, or CCDs. Your digital camera uses CCDs, too, though they're much smaller. And where your pocketable camera might be rated at 8 megapixels, Kepler's telescope weighs in at 95 megapixels.

Kepler's unblinking eye will scan a wider area than most astronomical telescopes, according to NASA. Where those devices see an area equivalent to a grain of salt held at arm's length, Kepler sees the whole hand at that distance.

According to a report issued this week by the Government Accountability Office, the Kepler project's total cost as of December was $595 million. Yes, that's more than was originally budgeted for it, and yes, it's launching about nine months behind schedule.

But for the moment, let bygones be bygones. Friday morning, NASA reported that the weather forecast in Florida is auspicious for tonight's launch: a 95 percent chance of favorable conditions, with a temperature of 64 degrees.